“Oh, you’re a villain, alright. Just not a super one!”

Megamind (2010)

From that scummy merchant selling overpriced healing potions to the eldritch horror trying to devour the gods, D&D villains are essential to every GM’s campaign. There’s nothing like a Big Bad that still has your players talking weeks after a session. But…there’s also nothing quite as painful as having a villain fall flat.

So, what makes a TTRPG villain stand out amongst the rest?

Well, first, let’s dive into what makes a villain work in traditional media.

Motivation → They always have strong motivations. It is crystal clear to the audience what the villain believes, and they believe it with their whole being.

Righteousness → A strong villain can justify why they’re doing what they’re doing. It might be absolutely insane to a normal person, but in the villain’s mind and story, it sounds like a logical step.

Persistence → They never stop pursuing their goals, no matter the obstacle. Honestly, they wouldn’t be much of a villain if the second a cop came knocking they threw their hands up and surrendered.

Aesthetic → Striking character designs are always memorable. Cosplayers wouldn’t exist otherwise.

Sympathetic (optional) → Some villains have backstories that make the audience (or even the hero) feel bad for them. When executed well, it creates an emotional conflict that forces audiences to weigh their morals against their empathy.

As an exercise, think of some villains you love. Break their pieces down according to the above list and note where your favorites excel and where they might be lacking. Figure out what makes a villain appeal to you.

When we turn to TTRPGs, the bar shifts slightly. GMs have to figure out how to effectively communicate who their villains are to players who are tracking at least ten too many things. There’s no convenient jumpcut to the villain abusing their lackeys in an underground layer as they laugh evilly over a pit of lava. The players’ experience informs how vile a villain feels.

So, then, how do GMs make a TTRPG villain great?

Personality & Mechanics

Personality

Motivation → Just like a villain in traditional media, TTRPG villains have strong motivations that are clear to the players.

Righteousness → TTRPG villains, like other villains, should be able to justify why they’re committing evil acts.

Characterization → Delivering information about the villain is crucial since TTRPGs are interactive mediums. Playing with direct and indirect characterization tells the players about the villain, often in a way they can engage with instead of a long lore drop.

Mechanics

Table presence → A GM can really bring a villain to life with voice acting, body language, and deliberate changes in behavior. Fully committing to the act always elevates the experience of any NPC, but especially a villain.

Ruthlessness → In combat and RP, a villain should always be going for the throat. Villains are meant to be scary, so, as the GM, don’t be afraid to instill the fear of god in your players.

Stat Block → To make a TTRPG villain stand out, use unique stat blocks for familiar villains. Make the normal feel fresh and new again by giving monsters unique abilities and strategies.

Homebrewing monsters is not a requirement. In fact, for most instances, it would be better to repurpose existing stat blocks.

This can be hard to visualize even after breaking down iconic villains into their many parts. Traditional media has an entire industry behind it that helps to make those villains exceptional. And, they don’t have to worry about their audience interrupting a monologue to announce they’d like to cast fireball. So, Liv and I have taken some of our strongest villains and broken down what made them so fun at our tables. Click through the names below — some of which you’ll recognize from our panel The Epic Highs and Low of D&D Villainy — to get a sense of some ways you can apply these concepts at your table.

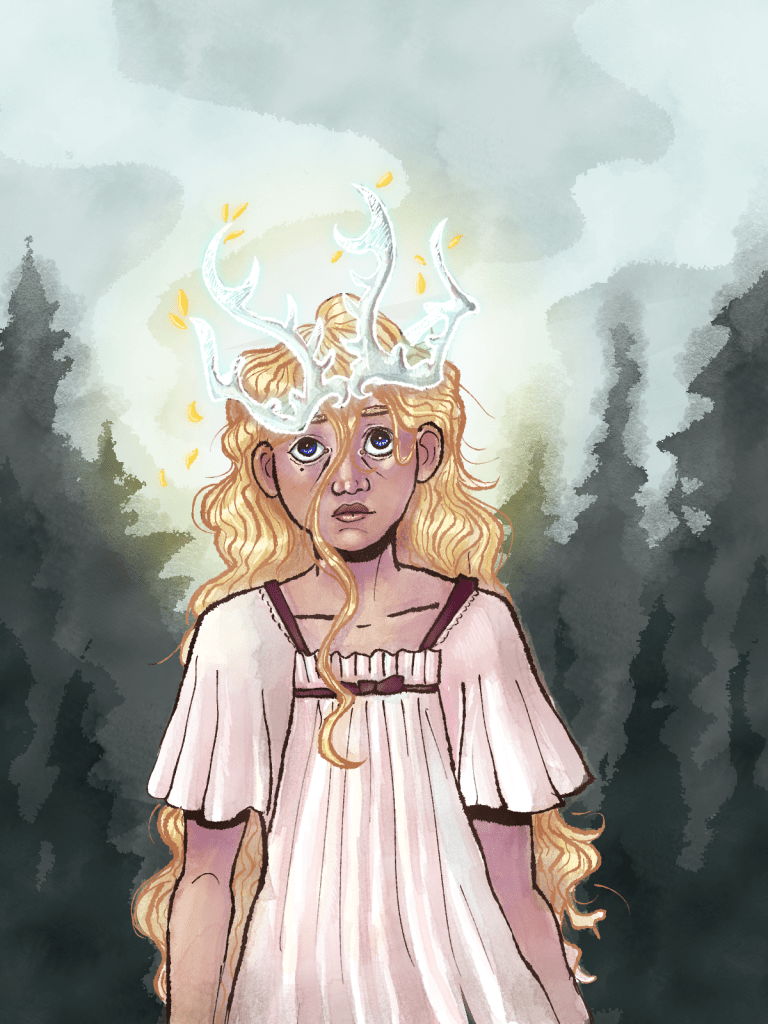

Queen Aria Whitehorn

Queen Aria Whitehorn is an exercise in misdirection, in how to use the power of indirect characterization to mislead players before they actually meet a villain.

Throughout the party’s time in this cursed kingdom, they heard of horrible deeds that the Queen had committed. She chopped down their sacred tree, turned it into a magical artefact, and then began to torture her citizens using her newfound power. Worse, once she turned evil, the Queen stopped allowing travelers passage, something the party desperately needed.

As they traveled closer to the castle, the realities they encountered supported the rumors. Most of the castletown had been flooded. The surviving citizens mutated into disgusting instrument hybrids, dying slowly and painfully in the process. A once beautiful kingdom was rotting from the inside out.

When the party finally snuck into the castle, they encountered Queen Aria Whitehorn, who had only just turned twelve years old. She explained that her mother was the queen who created this all-powerful artefact, and the power drove her mad. Young Aria inherited the kingdom, its cursed crown, and a gripping sense of paranoia of going crazy like her mom.

Though Queen Aria wore the crown, she could not control it. The reality-altering crown responded to Aria’s fearful wishes — to not be alone, for the castle to not be quiet — into the horrors that the party encountered outside. Even Aria was sitting alone in a castle full of undead servants as scared as her citizens.

Aria’s predicament tore the party in half. The justice oriented characters did not care that she was a scared child, highlighting the atrocities she has still committed against her own citizens for personal comfort. Others who empathized with Aria’s fear and naivety insisted that killing a child wouldn’t actually solve anything except creating another dead body. Even out of game, the players argued over how to handle this dilemma!

This tension is what made Aria Whitehorn so memorable. The indirect characterization painted a picture of a vicious queen with no regard for her kingdom while the direct characterization of the queen told the story of a young child thrust unprepared into a seat of power. The sympathy generated by Aria’s plight exacerbated the conflict between PCs and players alike.

By contrasting direct and indirect characterization, antagonists and villains can mislead players, PCs, NPCs, and many others.

Motivation: I don’t want to go crazy like my mom did, so I’ll drown out the voices with music

Righteousness: …self explanatory

Characterization: Turned her OWN CITIZENS into undead instruments, flooded her city so they couldn’t abandon her, and exiled anyone who disagreed

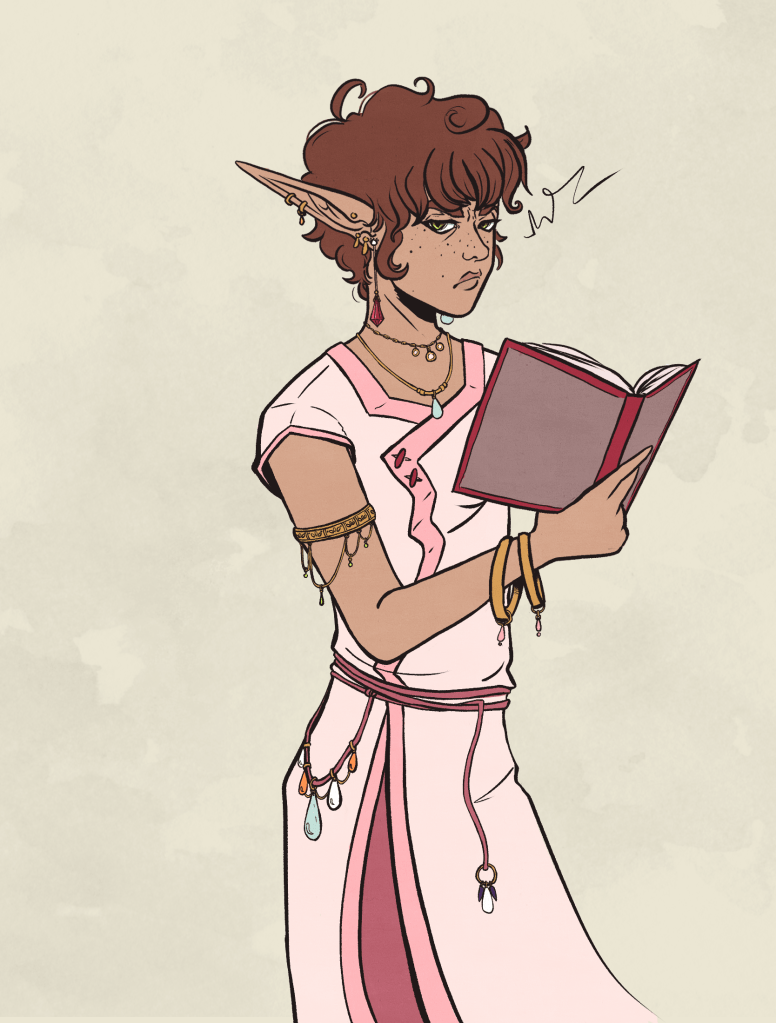

Roran Kriska

Roran Kriska is an example of how to make a small antagonist equally as hateable as your Big Bad. Their table presence makes them a miserable person to be around, and the players love to hate them.

See, when Roran was introduced at the table, they were meant to be a weak link in an otherwise sprawling social network of minor antagonists and villains. They were meant to be scared easily, and by design, their character flaws led to them making dumb mistakes that gave the players an edge against the Big Bad. However, they couldn’t be incompetent if they were supposedly hand-picked by the Big Bad.

Instead, they have flaws — a massive ego, an attitude, and shaky confidence.

This means that Roran will spill secret information just to prove they’re right. They don’t particularly try that hard to hide their notebook full of brilliant, evil schemes. They’re easily scared when directly confronted, but still make the party’s life difficult from behind the scenes.

But, they’re also plain rude. Not in an overt insult-slinging, name-calling, cursing way, but more subtly. Their tone is condescending. Their pauses are deliberate. They refuse to make eye contact with anyone they deem as lesser (so the whole party).

In order to benefit from any of their mistakes, the party has to tolerate Roran calling them dumb and ugly. By making Roran indispensable but also terrible to be around, they have become a lightning rod for animosity from the party. They ask if Roran is around every time they enter a new city, hoping and simultaneously dreading that the answer will be yes.

Any NPC could have delivered the same information, but the party wouldn’t despise them in the same way. Roran’s table presence is what makes them so memorable. They are your passive aggressive coworker, the worst woman at Church service, the kid who showed up to every college class in a suit and thought it made them important for some reason.

By leaning into your table presence, antagonists and other NPCs can elicit strong reactions from players, even if they don’t actually do anything heinous.

Characterization: Works for the BBEG, bullied by peers but beloved by adults, presents themselves as very anxious but is horribly out of pocket, as two faced as they come

Ruthlessness: They’re looking to get the party in trouble at all times

Table Presence: Acting out the real meaning of what they say, even if their words should be nice — eye contact, tone, and pauses!